Ying-Yai Sheng-lan (The Overall Survey of the Ocean’s Shores [1433])

MECHANICSVILLE, Va.—For much of its history, China had been an insular, rather xenophobic nation. There had been attempts, often successful, to subdue neighboring nations, but much of that aggressive spirit the past two millennia had been driven by outside invaders such as the Mongols who conquered, then were assimilated into, the Chinese people and who eventually redirected their attentions inward.

An exception to the outsider-driven outward gaze of the Chinese people came early in the Ming Dynasty—ironically, the last dynasty ruled by ethnic Han Chinese. The third Ming ruler, the Yongle Emperor (1402-1424), who seized the throne after deposing his nephew, the Jianwen Emperor (1398-1402), turned to a cadre of palace Eunuchs to help administer his government after a purge of Confucian scholars potentially loyal to his nephew.

One of those eunuchs was Zheng He (also romanized as Cheng Ho), a Muslim with considerable diplomatic, maritime, and military skills. The Yongle Emperor appointed him as admiral of a vast fleet of nearly 4,000 warships, transports, and treasure ships (Mills 1970a) and dispatched Zheng He on six expeditions (1405-1407, 1407-1409, 1409-1411, 1413-1415, 1417-1419, and 1421-1422) throughout the Indian Ocean and the seas immediately east and south of China.

The Yongle Emperor ordered the end of the expeditions late in his reign, but his successor, the Hongxi Emperor (1424-1425) dispatched Zheng He on a seventh and final expedition (1431-1433), but subsequently ended the expeditions for good and ordered that the ships be burned. (The emporer also ordered that a lot of land-based frontier trade be halted, too.) Zheng He himself may have died during the seventh voyage.

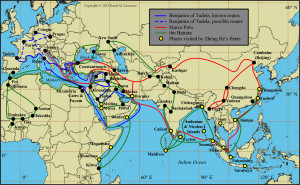

Map of the routes taken by several Middle Age explorers of the Old World. Tracks in blue are those of the twelfth century Jewish explorer Benjamin of Tudela; tracks in red are of the thirteenth century Christian explorer Marco Polo; tracks in green are of the fourteenth century Muslim explorer ibn Battuta; and yellow circles are some of the places written about by Ma Huan, himself a Muslim, in his account of the expeditions led by the Chinese admiral Zheng He in the 15th century. The religions of the explorers are important, as each man viewed the the lands and seas he traveled through with a different cultural lens. Redrawn from other sources. Mercator Projection with a nominal scale of 1:67,500,000.

Zheng He, while in command of the expeditions, did not go everywhere his ships did. He often dispatched smaller groups from the main fleet to visit additional locations. As far as is known, he left no personal account of his voyages. It is possible that he left reports that were subsequently purged from the Imperial record.

Some of Zheng He’s subordinates did leave accounts of the voyages, however. One of these was Ma Huan. Ma Huan referred to himself as a “mountain woodcutter,” but it is clear he was more than that. Like Zheng He, Ma Huan was a Muslim, and educated in reading and writing Arabic as well as Chinese script. He was employed as a translator on three of Zheng He’s voyages (1413-1415, 1421-1422, and 1431-1433).

Like Marco Polo or Ibn Battutah, Ma Huan’s narrative is somewhat uneven. Some places that stood out in his memory were described in great detail while others received just the briefest of abstracts. Here is an example of the latter, Ma Huan’s description of Li-tai—what is now Meureudu in Aceh Province, Sumatra, Indonesia:

The land of Li-tai is a also a small country. It lies on the west of the boundary with the land of Na-ku-erh [now Peudada]; south of this place there are large mountains; on the north it abuts the great sea [the Indian Ocean]; and on the west it joins the boundary of the country of Nan-p’o-li [now Aceh].

The people of the country [comprise] three thousand families. They themselves elect a man to be king, so that he may administer their affairs. [The country] is subject to the jurisdiction of the country of Su-men-ta-la [now Semudera].

The land has no products.

The speech and usages are the same as Su-men-ta-la.

In the mountains they have very many wild rhinoceros; and the king sends men to capture them.

[Their envoys] accompany [those from] the country of Su-men-ta-la to bring tribute to the Central Country [China] (Ma Huan 1970, 122).

Compare his meager description of Meureudu to the detail he gives of the Ka’aba in Mecca:

All around it on the outside is a wall; this wall has four hundred and sixty-six openings; on both sides of the openings are pillars all made of white jade-stone; of these pillars there are altogether four hundred and sixty-seven—along the front ninety-nine, along the back one hundred and one, along the left-hand side one hundred and thirty-two, [and] on the right-hand side one hundred and thirty-five.

The Hall is built with layers of five-coloured stones; in shape it is square and flat-topped. Inside, there are pillars formed of five great beams of sinking incense wood, and a shelf made of yellow gold. Throughout the interior of the Hall the walls are all formed of clay mixed with rosewater and ambergris, exhaling a perpetual fragrance. Over [the Hall] is a covering of black hemp-silk. They keep two black lions to guard the door.

Every year on the tenth day of the twelfth moon all the foreign Muslims—in extreme cases making a long journey of one or two years—come to worship inside the Hall. Everyone cuts off a piece of the hemp-silk covering as a memento before he goes away. When it has been completely cut away, the king covers over [the Hall] again with another covering woven in advance; this happens again and again, year after year, without intermission (174-175).

I added Ma Huan’s account of the Zheng He expeditions to my reading list in the hopes of getting a different—Asian—perspective on lands also visited by Benjamin of Tudela, Marco Polo and ibn Battutah. I did not feel that I got all that different a perspective, however. Given Ma Huan’s Muslim faith, he might not have been the ideal candidate for what I sought.

While Ma Huan had broader interests than Benjamin of Tudela—who seemed primarily interested in cataloging the Jewish communities encountered in his travels—Ma Huan was still not the storyteller that either Marco Polo or ibn Battutah were. The narratives by the latter two men conveyed a sense of adventure that that carries through nearly a millennium to infect and inspire twenty-first century readers. Ma Huan’s Overall Survey of the Ocean’s Shores strikes me as largely a mercantile account of the resources available and the political and economic systems encountered in the places they visited.

Nevertheless this was an interesting treatise from a brief period in history when China was not content focusing its national energy within its own borders. Modern readers should draw their own conclusions as to whether Overall Survey bears any relevance comparisons to the China of today.

REFERENCES

Ma Huan. 1970. Ying-yai Sheng-Lan (The Overall Survey of the Ocean’s Shores [1433]). Translated by J.V.G. Mills. London: Hakluyt Society. Reprinted Bangkok, Thailand: White Lotus Press, 1997.

Mills, J.V.G. 1970a. “Introduction: Cheng Ho and His Expeditions.” In Ma Huan, Ying-yai Sheng-Lan (The Overall Survey of the Ocean’s Shores [1433]), 1-34. London: Hakluyt Society. Reprinted Bangkok, Thailand: White Lotus Press, 1997.